History Snapshot –Wilder’s storied background from the 1920s to 1940s

The land that makes up Wilder on the Taylor, located between Gunnison and Crested Butte, Colorado, has a well-earned ranching heritage that took root in 1893, when three young men filed claims for homesteads. A previous article, Taylor River Ranch : A Storied Background Dating Back 100 years, is based on a book written by William R. Simon and published by Wilder in 2017, provided an overview of the events leading up to homesteading through ownership by the Al and Mabel Roper and Bill and Agnes Redden.

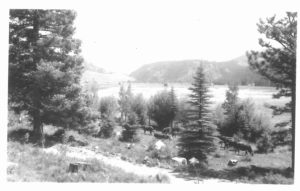

This second article in this history series picks back up in 1920, when ranchers in the Spring Creek area, including the Wilder valley, formed the Spring Creek Cattle Growers’ Association (SCCGA). The organization dedicated itself to protecting “the interests of the members of this association; to secure equitable and just legislation and grazing regulations; and to work in cooperation with the Forest Service in the protection and economical use of all products of the National Forest.”

It’s important to understand what led up to the establishment of SCCGA. In the early days of ranching, the availability of free fodder on public land brought phenomenal growth to cattle ranching and prosperity to Gunnison stockmen. But it came with a price: overgrazed grasslands devastation.

It’s important to understand what led up to the establishment of SCCGA. In the early days of ranching, the availability of free fodder on public land brought phenomenal growth to cattle ranching and prosperity to Gunnison stockmen. But it came with a price: overgrazed grasslands devastation.

President Theodore Roosevelt addressed the issue in 1905 by establishing the Gunnison Forest Reserve and four other Colorado reserves. Two years later, the name Forest Reserve was changed to National Forest. Withdrawing the land from unrestricted public use and placing it under the management of the United States Department of Agriculture and its newly created Forest Service protected it from further exploitation.

The new government agency intended to accomplish its mission to “sustain healthy, diverse and productive forests and grasslands for present and future generations” with a multiple-use program that made the land available for both economic and recreational users.

The imposition of federal regulation ignited a firestorm of protest from Gunnison ranchers. Anger turned to fury in 1906 when the government implemented a grazing tax program requiring cattlemen to pay from 25¢ to 35¢ per head during the regular season. But the national tide favoring natural resources management could not be stopped. The free-range grazing days were over. When the U.S. Supreme Court upheld regulated grazing and timber management of the National Forests in 1911, much of the open hostility subsided.

Bill Redden, who served as vice president, and the other association members, demonstrated their willingness to cooperate with the government on mutually advantageous projects. One such effort resulted in a range improvement agreement with the Forest Service in 1930. Both parties agreed, among other things, that eradication of larkspur, a native plant toxic to cattle, was a good thing, and that Spring Creek cattle wandering into other grazing allotments was a bad thing. The stockmen agreed to foot the bill for the eradication and for building drift fences to keep the herds in check.

Ranch living required creativity and hard work

Ranchers were of course just as concerned about the well-being of their families, and fortunately, food was fairly plentiful. The Reddens kept potatoes from their three-acre patch in a root cellar along with apples and canned peaches, pears and cherries they purchased on summer buying trips to fruit orchards in Delta and Montrose.

The Ropers depended on produce and cattle they raised. “We had a big garden,” recalled Mabel Roper, “and made and canned kraut, raised our own potatoes and sometimes had a few to sell. We’d butcher calves and trade the meat for groceries. Sometimes we would even get ahead, and they would owe us for groceries.”

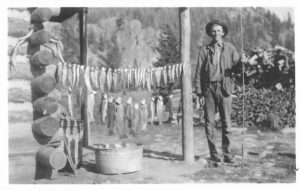

However, money was scarce, so bartering was common. Harvesting what grew wild was another way to stretch budgets and conserve cash. Al Roper trapped grasshoppers in his hat and used them for bait to catch fish on the Taylor. Venison, however, was the family’s preferred food choice.

However, money was scarce, so bartering was common. Harvesting what grew wild was another way to stretch budgets and conserve cash. Al Roper trapped grasshoppers in his hat and used them for bait to catch fish on the Taylor. Venison, however, was the family’s preferred food choice.

Trout and venison appeared frequently on the Redden menu, too, readily abundant and easily obtained. Maggie Redden remembered, “If you needed some meat, you stepped out to the back doorstep and shot one of those darn deer that was out there in the hay meadow. We always had venison. It seems strange. Dad raised beef, but we grew up eating venison.”

Paul Redden witnessed his father’s impressive angling forays on the Taylor, seeing his dad “catch 40 fish in a couple of hours and think nothing of it. That’s what we ate. That was our meat in the summertime.”

Al eventually found the financial strain of maintaining the Taylor River ranch and a house in Gunnison, where his family stayed during the school year, unsupportable. In 1929, the Ropers sold 72.70 meadow acres to the Reddens for $7,000 and the remainder of their land, mostly hillside acres, to the Elmer family. Working for others and living in town was not a good fit for Al’s independent spirit, so in 1931 he traded their house and borrowed $4,000 for a ranch on the Gunnison River three miles south of Almont.

Al eventually found the financial strain of maintaining the Taylor River ranch and a house in Gunnison, where his family stayed during the school year, unsupportable. In 1929, the Ropers sold 72.70 meadow acres to the Reddens for $7,000 and the remainder of their land, mostly hillside acres, to the Elmer family. Working for others and living in town was not a good fit for Al’s independent spirit, so in 1931 he traded their house and borrowed $4,000 for a ranch on the Gunnison River three miles south of Almont.

When cattle prices plummeted and with a larger ranch to manage, Bill Redden countered with entrepreneurial initiatives, landing a roadwork contract with the county to improve Taylor River Road (County Road 742) from the ranch to Taylor Park.

“I can remember my dad working on the road,” said Maggie. “He had a horse-drawn road grader that he hooked to two teams of horses.” Scoops and slip scrapers also were used to remove boulders and clear the road.

Reddens introduce tourism to the ranch

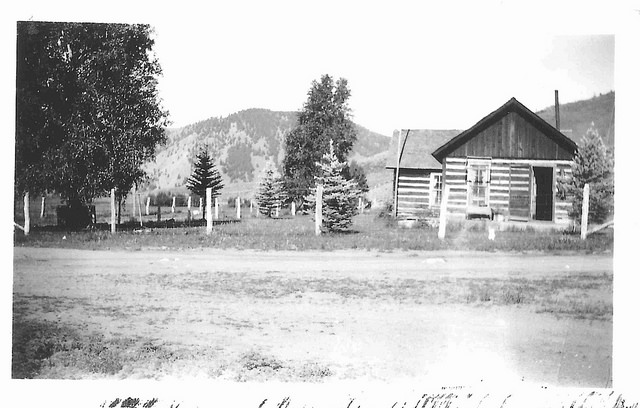

The Reddens reaped the largest rewards, however, from tourism. The success of Elmer’s River Resort just the down the road (now Harmel’s Ranch Resort) and the fact that the Reddens owned two miles of prime private fly-fishing riverfront inspired Bill to build tourist cabins along their stretch of the Taylor River in 1936. The cabin interiors were spare: one large room with two beds at one end and privacy provided by a curtain strung on baling wire between beds and the rest of the room. Amenities included a wood cook stove, icebox, table and chairs, and a nearby outhouse. Water was drawn from a community well.

At a cost of $1.50 per night, the cabins attracted Colorado customers from Pueblo, Colorado Springs and Denver. Summer heat also resulted in several Oklahoma families flocking to the ranch, including Sue Caston Foltz’s, who rented a cabin beginning in 1938. The men fished (the limit was 20 fish a day per license), and the women cooked. There were also picnics, campfires and sing-a-longs in the evenings, and Sue remembered playing with the Redden children.

When things got busy, Kate Redden’s homestead house and the family’s bunkhouse were rented if they didn’t have a hired hand living there at the time. The business model included profitable tourist add-on sales from milk, cream, butter and cottage cheese. Also, worms were available for 1¢ each and ice for 1¢ per pound. The ice was sawed into blocks from winter ponds and stored in a sawdust-insulated icehouse over the summer.

When things got busy, Kate Redden’s homestead house and the family’s bunkhouse were rented if they didn’t have a hired hand living there at the time. The business model included profitable tourist add-on sales from milk, cream, butter and cottage cheese. Also, worms were available for 1¢ each and ice for 1¢ per pound. The ice was sawed into blocks from winter ponds and stored in a sawdust-insulated icehouse over the summer.

Water, electricity and war

The Taylor River canyon, where the ranch is located, lost a portion of its isolation with the completion of the Taylor Park Dam and Reservoir in 1937. Built and managed by the U. S. Bureau of Reclamation, the reservoir controlled the seasonal fluctuations in the flow of the Taylor and Gunnison Rivers. John Roper recalled that “the only way we could increase the amount of water available for ranching and farming was by saving the spring runoff.” When the construction crews cleared out at project’s end, they left an unimproved road through Taylor Canyon along the river and a new tourist attraction for boaters and fishermen.

There was more cause for celebration in 1942 when Gunnison County Electric Association (GCEA), a nonprofit cooperative, threw the switch that delivered power to the Wilder valley. Made possible by the New Deal’s Rural Electrification Agency (REA), few objected to the intrusion of big government when it offered a helping hand that made hard times easier.

World War II formally ended on September 2, 1945, when the Japanese signed the Instrument of Surrender aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. The country’s economic prospects presented a brightly-lit future, and one of its ripples found Al Roper, who used the financial windfall to splurge on a previously unattainable big-ticket purchase: a 1946 Oldsmobile.

Meanwhile, Bill Redden imagined a larger future for his family. Beef prices were up and likely to stay there for some time, but the Redden ranch had no capacity for expansion. It was time to sell. Samuel Wolfe, a 27-year-old war vet, bought the property in 1946, and proceeds from the sale enabled the Reddens to acquire a 2,000-acre ranch on Ohio Creek. A few years later, they increased holdings with the addition of a second ranch. Eldest sons Tom and Wilbur took over their ownership and operation following Bill’s death in 1964.

Make sure to catch the next article for more information about the Wolfes, Leonards and the next part of the Wilder story!

To learn more about the modern day Wilder and its Crested Butte land for sale, visit https://wildercolorado.com/