History Snapshot – Two Families & a Cattle Company Continue Wilder Legacy

This is the third in a series of articles that chronicles the rich history and storied background of Wilder on the Taylor, a ranch located between Gunnison and Crested Butte, Colorado that dates back to homesteading days in 1893. The series is based on a book written by William R. Simon and published by Wilder in 2017, with the previous article looking at the 1920s through the mid-1940s. In this installment, find out about the Wolfes, Leonards and a cattle company that helped define the ranch for the next four decades.

After World War II

Military service had reinforced Samuel Wolfe’s loathing for authority, and he sought a future of his own choosing. Purchasing the ranch along the Taylor River from Bill Redden in 1946 provided that autonomy. What the 27-year-old war vet lacked in experience he made up for in persistence, physical stamina and mechanical ability. He adapted easily to the ranch culture of the era. If something broke, he fixed it. Wolfe spent countless hours in his repair shop and over a forge. What he couldn’t figure out on his own, he learned from others.

Roy “Sandy” Dunbar, the former teamster-turned-rancher who owned a hay and cattle property about four miles below Wilder, became a friend who generously shared his ranching knowledge. The two men served as officers of the Spring Creek Cattle Growers’ Association, Dunbar as president and Wolfe as secretary/treasurer.

Sam met his future wife, Lynne, while she and her two young children lived at a small resort on Spring Creek. Her son, Swain, who later took his stepfather’s last name, was 10 when the couple married in 1949 and his family moved to the ranch.

In a memoir, Swain recalled Spring Creek ranchers rounding up their summer-grazed herds in the fall and branding the late calves before bringing them down from the high country. Fall was also the season for selling steers as well as cows that were no longer producing calves. The cattle that remained over the winter relied on the ranch’s hay crop, usually harvested in August.

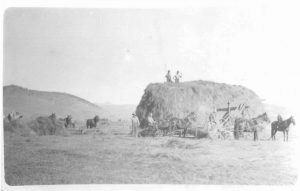

Swain considered it his good fortune to have witnessed the end of an era before the internal combustion engine replaced horses on Taylor River ranches. “With a little guidance from Sam,” he wrote, “I learned to operate every horse-drawn machine we had. We cut and stacked hay in two large fields separated by the lane that ran from the house and barns down to the river.”

Swain considered it his good fortune to have witnessed the end of an era before the internal combustion engine replaced horses on Taylor River ranches. “With a little guidance from Sam,” he wrote, “I learned to operate every horse-drawn machine we had. We cut and stacked hay in two large fields separated by the lane that ran from the house and barns down to the river.”

The relationship between Sam and Lynne became difficult, resulting in Lynne and the kids moving to Montana. The couple reconciled, and Sam agreed to sell the ranch and join them. Before a buyer could be found, he put the ranch up for lease in 1953.

Cass and Anita Leonard, who worked a nearby cattle spread, drove over to take a look. Cass had grown up on a homestead ranch near Doyleville, Colorado, approximately 20 miles east of Gunnison, and liked that Wolfe’s ranch land was still remote and wild. Ten days later, the couple and their two children (Ron, 6, and Kerry, 4), moved into the ranch house.

The Leonards & Elsinore Cattle Company

Life on the Taylor began well for the Leonards. At the end of their first growing season, the hay stood taller than Anita, who grew up in Texas near Abilene as the daughter of cotton farmers. A big crop, however, did not improve the couple’s overall financial capacity. Wolfe’s offer to sell them the property for $85,000 exceeded their means. Instead, Elsinore Cattle Company purchased the ranch in 1954 and asked Cass to manage its operation. It was a good arrangement for Cass and Anita as they lived their ranching dream for 34 debt-free years and avoided the downside when the ranch failed to make a profit in later years.

The history of Elsinore Cattle Company is the story of Edwin W. Giddings and William O. Lennox, two Colorado Springs businessmen who formed a partnership and invested in the 1890s Cripple Creek gold mining boom. Although the history of Colorado mining abounded with failure and disappointment, they defied the odds and struck it rich.

The partnership continued as the men expanded their portfolio to pursue other profitable ventures, including a cattle ranch located near Fort Stockton in west Texas in the early 1900s. Elsinore was a good-sized spread even by Texas standards with more than 200,000 acres.

Giddings and Lennox continued their business and personal friendship over the years, as did their descendants. By the early 1950s, when the number of shareholders had grown to 40, the ranch managers came up with a way to counter the cattle operation’s arid location: buy a Colorado ranch with abundant water and good forage, ship in Texas yearlings, graze the cattle over the summer, and sell them in the fall. The weight gain, they believed, would offset expenses and turn a profit.

Giddings and Lennox continued their business and personal friendship over the years, as did their descendants. By the early 1950s, when the number of shareholders had grown to 40, the ranch managers came up with a way to counter the cattle operation’s arid location: buy a Colorado ranch with abundant water and good forage, ship in Texas yearlings, graze the cattle over the summer, and sell them in the fall. The weight gain, they believed, would offset expenses and turn a profit.

Elsinore agreed to pay Cass $475 a month plus one cow a year, use of the house, utilities and fuel. As for potential problems associated with multiple owners, Cass resolved that issue early on when he told them: “You guys decide who’s going to be boss, and I’ll work under him, but I’m not working under 40.”

The Leonards ran the ranch as if it was their own, and all management decisions rested with Cass. Like many farm families, they stretched their dollars by adding dairy cows and selling extra milk and cream to neighbors. They also raised chickens and pigs.

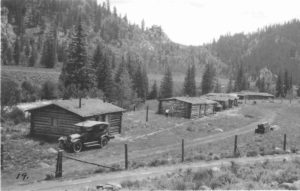

Most of the owner families preferred traditional recreation rather than the cowboy lifestyle when visiting. They expanded the ranch’s riverside accommodations by converting the eight riverside tourist cabins into four by joining two cabins together with a connecting hall. Even with the added space and other remodeling upgrades, Bruce Jansson remembered them as “amazingly rustic and simple, but that made it all the more fun as far as I was concerned.” He added, “Fishing, hiking, being outdoors in that beautiful country is what I remember most. Living right on the river was such an astonishing experience.”

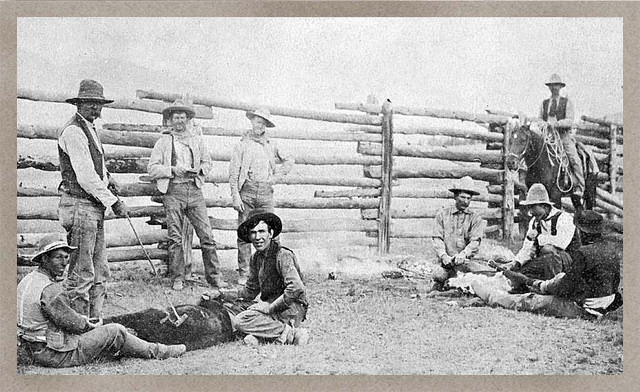

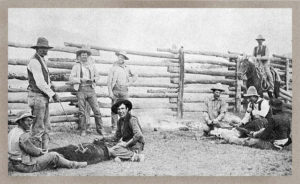

The task of branding 600 to 800 steers that arrived each spring required extra hands, so Cass scheduled the work on Memorial Day weekend. “Branding was a big event,” said Ron Leonard. “Everyone helped, all of our family, women, kids, some owners, and lots of friends. Dad and I did all the branding, castrating and dehorning while others kept the pens full, ran the chutes, pushed in the steers and vaccinated.” After branding Cass assembled another group of volunteers to drive the cattle to summer pasture.

Kerry Leonard looked forward to Cattlemen’s Days and 4-H, but had few regrets about the 17 miles separating her from these activities and others available to town kids. She and Ron found endless adventure at Elsinore. “We never said, ‘Mom, we don’t have anything to do.’ It was almost like a fairy tale. The ranch was so beautiful, and it was so much fun. I didn’t realize how awesome growing up there was until I got older and moved away,” she said.

Connection to community

Cass held active memberships in the Colorado Cattlemen’s Association and its affiliate, the Gunnison County Stockgrowers’ Association, for 20 years, serving as president of both. The Gunnison Chamber of Commerce named him “Rancher of the Year” and Anita as “Gunnison County Master Farm Homemaker” in 1978.

However, Cass devoted the largest amount of his volunteer work (43 years worth) to Cattlemen’s Days in Gunnison, servicing as racing chairman, racing judge, director and president. In 1993, the year of his death, a memorial was installed at the entrance to the community’s county fair and rodeo grounds where a plaque reads in part: “For his love of and dedication to ranching, rodeo, youth and the Gunnison Valley.”

Anita’s community contributions complemented her husband’s. She served as Cattlemen’s Days racing secretary for 20 years and led All Thumbs and Little Crumbs, a girls’ 4-H club oriented toward sewing and cooking. Volunteer service with a beef promotion organization, the Gunnison Valley Cowbelles (later changed to Cattlewomen), stoked Anita’s activist spirit. During her two-year presidency in the mid-1970s, she encouraged women to step out from behind traditional roles.

A changing economic landscape

Gunnison County began witnessing a historic change as ranching no longer dominated the local economic landscape. The turning point for tourism’s climb to preeminence began in the early 1960s with the development of a ski resort in Crested Butte. A decade later, the ski area and East River Valley entered a boom phase.

Ranchers felt the impact of skyrocketing real estate prices as outside money poured into the area. Cattlemen struggling to hold on to a middle-class lifestyle in the face of low profit margins and rising costs suddenly discovered their land was worth a fortune. “When a rancher can sell one plot of land for what he could make in 10 years raising cattle—what can you do?” Anita observed in 1976.

Agriculture also dwindled as increasing numbers of ranch children took advantage of higher education and pursued other careers.

Over the years, interest in the investment waned, and the owners finally agreed the great Colorado ranch should be sold. In addition to land conservation groups and ranchers, a new breed of second-home owners began to take an interest in the preservation of open spaces like the Elsinore Ranch and other ecological issues.

Sonny Brown, an avid fisherman and hunter, owned a home six miles above Elsinore at Crystal Creek and became aware that Elsinore owners were motivated to sell. He made a cash offer that was accepted in 1988 and renamed the property Wapiti Canyon Ranch.

The next article will look at how the ranch progressed from this point forward and later became known as Wilder on the Taylor.

To learn more about Wilder on the Taylor and Crested Butte land for sale, visit https://wildercolorado.com/